|

|

|

|

|

Hyracotherium

These small ancestors of modern horses were half a metre or less in length -- about the size of a fox terrier. Compared

to living horses, their legs were shorter, they had longer heads

relative to their bodies, and a more complete series of teeth. They

had three toes on their hind feet and four on their forefeet. Each

toe had a pad on its underside, like dogs have. Modern horses have

long legs, each ending in a single, powerful toe with a hoof -- but

no pad. Eohippus lived during the early part of the Tertiary (about

50 million years ago). Although these dawn horses were present in

Europe as well as North America, the mainstream of horse evolution

occurred on the latter continent. |

|

EXCERPT: Stephen Budiansky's new book, The Nature of Horses

In a chapter about

the evolution of the horse he talks about the evolution of size and

speed:

"The usual explanation for these changes, and for the eventual

appearance of the single-toed foot in Pliocene horses (beginning 5

million years ago) is that, as grassland animals, these grazing horses

were more exposed to predators and had to be able to flee. The

evolution of the diastema may be related to this fact too: a long

distance between the front of the mouth and the eyes allows an animal to

graze and keep an eye out at the same time.

There is no doubt that larger animals are faster and that the springing

hoof allowed for a faster gait. The almost unbelievable discovery

of fossil footprints of three Hipparion horses from the middle Pliocene

(3.5 Million Years ago) have provided ample confirmation of the sped and

agility of these grasslands-adapted horses. Although Hipparion

still had three toes on each foot, it had already developed the

springing foot mechanism; and in spite of its relatively small

size, its overall proportions-leg length relative to body size, for

instance- are quite similar to those of modern horses.

The two side toes

in Hipparion species, while able to help balance the foot and even add

some to the locomotive effort, were already much reduced in size

compared to those of their ancestors, and clearly most of the work was

done by the large central toe. The Hipparion footprints, made in

soft lava subsequently covered with volcanic ash, were discovered in

Tanzania by Mary Leakey in 1979, along with trails of a number of other

mammals, including early hominids.

|

|

A subsequent analysis of the horse footprints makes a convincing

case that these Hipparion horses traveled a good clip utilizing

the gait known as the running walk-the

characteristic gait of Tennessee waking horses, Icelandic ponies,

and Paso Finos, in which the length of the stride is extended and

only one or two feet are in contact with the ground at any given

time. Comparison of the fossil footfalls with the footfall

patterns of Icelandic ponies suggests that one of the Hipparions

was traveling at 15 kilometers per hour. The two trails

appeared to be those of a mother and foal, the latter

crisscrossing the path of its mother in much the same fashion as

is observed in modern horses.

The finding incidentally provides at least some

suggestive evidence in support of the contention that the running

walk, though associated with only certain breeds these days, is

nonetheless an instinctive and natural gait, rather than (as is

sometimes argued) one that is artificial and man-taught" . |

|

|

|

The Tennessee

Walking horse carries the blood of four distinct living breeds - the

Thoroughbred, Standardbred, American Saddlebred, and the Morgan, plus

two breeds that are virtually extinct - the Narragansett Pacer and the

Canadian Pacer. While English Thoroughbreds, Morgans,

Standardbreds and coach horses may all be found in the background of

Tennessee Walking horses, it was the Canadians and Narragansetts who

formed the basis for their gaits. The two earliest strains,

or breeds, of horses recognized in North America were the Canadian

Pacer, a breed still existing in small numbers in Canada, which evolved

from Norman horses brought to Quebec by French settlers; and the

now-extinct Narragansett Pacer, which evolved from British Hobbies and

Galloways brought to the American Colonies by English settlers.

|

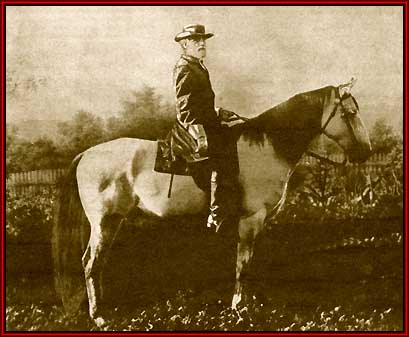

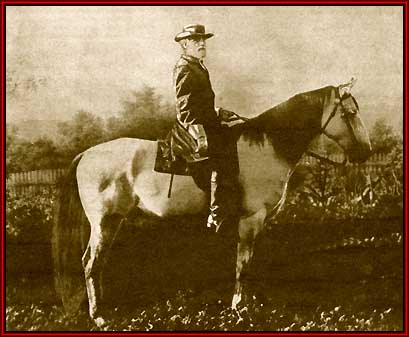

TRAVELER, 1861 (General Robert E. Lee up)

Bred in Virginia, Traveler was bought by General Lee in 1861.

His breeding was probably of Thoroughbred, Morgan, and Narragansett

blood,

which flows through so many well known Tennessee Walking

Horses. |

About 150 years ago in American history, when the

hill people of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee crossed the

Mississippi River to settle the Ozark Mountain regions of Missouri

and Arkansas, they took with them their best horses. The

square trotting horses were able to cover the ground, but their gait

was uncomfortable, and tiring for both horse and rider within just a

few miles. The "Walking Saddle Horse," or "Plantation Horse"

as the Tennessee Walker was called then, would do a running walk,

and that was fast and comfortable. While the bloodlines of the

Gray Johns, Copperbottoms, Slashers, Hals, Brooks and Bullett

families ran thick and produced a type known as the Tennessee pacer

prior to the arrival of Allan F-1 in Middle Tennessee, it was a cross

between Allan and the Tennessee Pacer that produced today's Tennessee

Walking Horse. At this time, the most prominent saddle horse was

the now-extinct Narragansett Pacer, which originated around Narragansett

Bay, in Rhode Island.

|

|

|

|

|

To the North in the Canadian Provinces, French mares

were crossed with English and Dutch stock, to produce what became

known as the Canadian Pacer, a breed which still exists, but in very

small numbers in that country.

|

|

|

Then, the American Colonists began crossing their

gaited stock with the English Thoroughbreds. One famous

stallion was Hedgeford, imported in 1832, and his most remembered

son was Denmark.

|

|

|

Denmark was bred to a mare of Narragansett

background known as the Stevenson mare, from Cockspur bloodlines,

and their foal was Gaines Denmark. During his career, Gaines Denmark

produced four legendary sons, and in 1908, the American Saddle Horse

Breeder's Association named him THE single foundation sire of the

Saddle Horse breed. Previous lists had included such horses as

Harrison Chief, Tom Hal and Copperbottom.

|

|

|

Understandably, as harness racing became popular

with Colonial gentlemen, these horses made their way towards the

colonies of Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee. Inevitably, as frontiers

moved south and west, the Narragansett and Canadian Pacers came

together. The Canadians went to New England, where they became a part of

the foundation of what is now the Morgan breed.

|

|

|

The Tennessee Walking Horse was derived in

Tennessee, primarily from the American Trotting Horse with the

heavy influence of the Morgan Horse and the Canadian Pacer.

The American Trotting Horse is now known as the Standardbred.

|

|

|

The war Between the States occasioned the

crossbreeding of the Confederate Pacer and Union Trotters: thus the

Southern Plantation Walking Horse or Tennessee Pacer came into

being. Next came the blood of the Thoroughbred,

Standardbred, Morgan and the American Saddlebred. All were

fused into one animal in the middle of Tennessee bluegrass region.

The result, over countless years, was the "world's greatest show,

pleasure, and trail horse,"- the first breed of the horse to bear a

state name - the Tennessee Walking Horse.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|